While antifeminists will probably have a field day with these results, the intent wasn’t to measure frigidity according to political stance, but to determine whether penile thrusting alone was an efficient way of inducing female orgasm. The results? More than three-fourths of the prostitutes had an orgasm, compared with only one in eight feminists. Heli Alzate, a physician and professor of sexology, and Mari Ladi Londoño, a psychotherapist, mustered 16 prostitutes and 32 feminists into their lab, where they manually stimulated their vaginal walls.

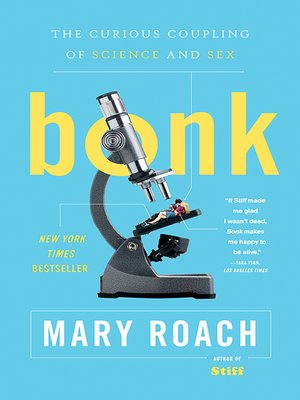

In a similar spirit, there’s the study on “labial traction as an instigator of female orgasm,” conducted by a team of Colombian researchers in the mid-1980s. This is “as good as science gets,” she writes, “a mildly outrageous, terrifically courageous, seemingly efficacious display of creative problem-solving, fueled by a bullheaded dedication to amassing facts and dispelling myths in a long-neglected area of human physiology.” She delights in medical euphemism and scholarly jargon you can hear her titter as she rolls out terms like “vaginal photoplethysmograph probe,” “nocturnal penile tumescence monitoring” and “vaginocavernosus reflex.” Writing about a 1950s-era study of vaginal response in which female subjects copulated with a penis camera, Roach wants to know how exactly the “dildo-camera” operated, who volunteered to make use of it in a laboratory setting and, above all, where the device is now. Roach belongs to a particular strain of science writer she’s interested less in scientific subjects than in the ways scientists study their subjects less, in this case, in sex per se than in the laboratory dissection of sex. Intended as much for amusement as for enlightenment, “Bonk” is Roach’s foray into the world of sex research, mostly from Alfred Kinsey onward, but occasionally harking back to the ancient Greeks and medievals (equally unenlightened). In “Bonk,” she turns to sex, covering such territory as dried animal excreta used as vaginal “drying agents” a rat’s tail “lost” in a penis and a man named William Harvey, patent-holder for a rolling toaster-size metal box outfitted with a motorized “resiliently pliable artificial penis.” In short, she takes an entertaining topic and showcases its creepier side.Īnd then she makes the creepy funny.

In her previous books, “Stiff” and a follow-up, “Spook,” Mary Roach set out to make creepy topics (cadavers, the afterlife) fun.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)